Introduction: Navigating the Complex World of Cancer

Cancer. It’s a word that touches nearly every life, evoking a spectrum of emotions and questions. For centuries, this complex group of diseases has posed one of humanity’s greatest health challenges. Yet, in the face of this complexity, knowledge emerges as our most potent tool. This blog post aims to provide a comprehensive, understandable, and hopeful overview of cancer. We will journey through its fundamental nature, explore its diverse forms, unravel its causes, and identify its warning signs. Crucially, we will delve into the intricacies of diagnosis, the evolving landscape of treatment, and the inspiring breakthroughs at the forefront of cancer research. Whether you are a member of the general public seeking foundational knowledge, a patient or family member directly impacted by cancer, or a healthcare professional looking for a consolidated perspective, this information is intended to empower. While the path of cancer can be daunting, the relentless pace of scientific discovery and medical innovation continues to illuminate the way forward, offering ever-increasing hope and improved outcomes.

Table of Contents

Understanding Cancer Fundamentals: What It Is and How It Develops

At its core, cancer is a disease characterized by the uncontrolled growth and division of abnormal cells. Our bodies are made up of trillions of cells that normally grow, divide, and die in an orderly way. This process is tightly regulated by instructions encoded in our DNA. However, when DNA within a cell incurs certain changes, or mutations, these instructions can go awry. This can lead to cells behaving abnormally – they may multiply when they shouldn’t, or they may not die when they should (Mayo Clinic).

These abnormal cells can form a mass of tissue called a tumor. Tumors can be benign (non-cancerous), meaning they do not spread to other parts of the body, or malignant (cancerous). Malignant tumors are dangerous because they can invade nearby tissues and spread to distant parts of the body through the bloodstream or lymphatic system. This process of spreading is known as metastasis. When cancer metastasizes, it can form secondary tumors in other organs, making it much harder to treat. Substances that can cause cancer by damaging DNA are known as carcinogens. As cancerous cells proliferate, they can disrupt normal body functions by crowding out healthy cells, interfering with organ function, and consuming vital nutrients.

Demystifying Cancer: Types and Classifications

Cancer is not a single disease but a collection of over 200 distinct diseases, each with its own characteristics, behavior, and response to treatment (Cancer Research UK). Cancers are primarily classified in two main ways: by the type of tissue in which the cancer originates (histological type) and by the primary site, or the location in the body where it first developed (SEER Training Modules).

Understanding these classifications helps medical professionals diagnose, treat, and research cancer more effectively. The main histological types include:

- Carcinoma: This is the most common type of cancer, accounting for about 80% to 90% of all cases (Cleveland Clinic). Carcinomas begin in the epithelial cells, which form the lining of organs and surfaces within the body. Examples include cancers of the lung, breast, colon, prostate, and skin.

- Sarcoma: These cancers arise from connective or supportive tissues such as bone, cartilage, fat, muscle, blood vessels, or other soft tissues. Sarcomas are much less common than carcinomas.

- Leukemia: Termed “blood cancer,” leukemia originates in blood-forming tissue, usually the bone marrow. It leads to the production of large numbers of abnormal blood cells that enter the bloodstream.

- Lymphoma and Myeloma: These cancers begin in the cells of the immune system. Lymphomas affect the lymphatic system (part of the immune system), while myeloma starts in plasma cells, a type of white blood cell in the bone marrow.

- Central Nervous System Cancers: These develop in the tissues of the brain and spinal cord.

In addition to histological type, cancers are also named based on their primary site. For example, cancer that starts in the lungs is lung cancer, and cancer that starts in the breast is breast cancer. Common examples of cancer types by site include Bladder Cancer, Breast Cancer, Colorectal Cancer, Kidney (Renal Cell) Cancer, Lung Cancer, Lymphoma, Pancreatic Cancer, and Prostate Cancer (National Cancer Institute – NCI).

Unraveling the Causes: Risk Factors for Cancer

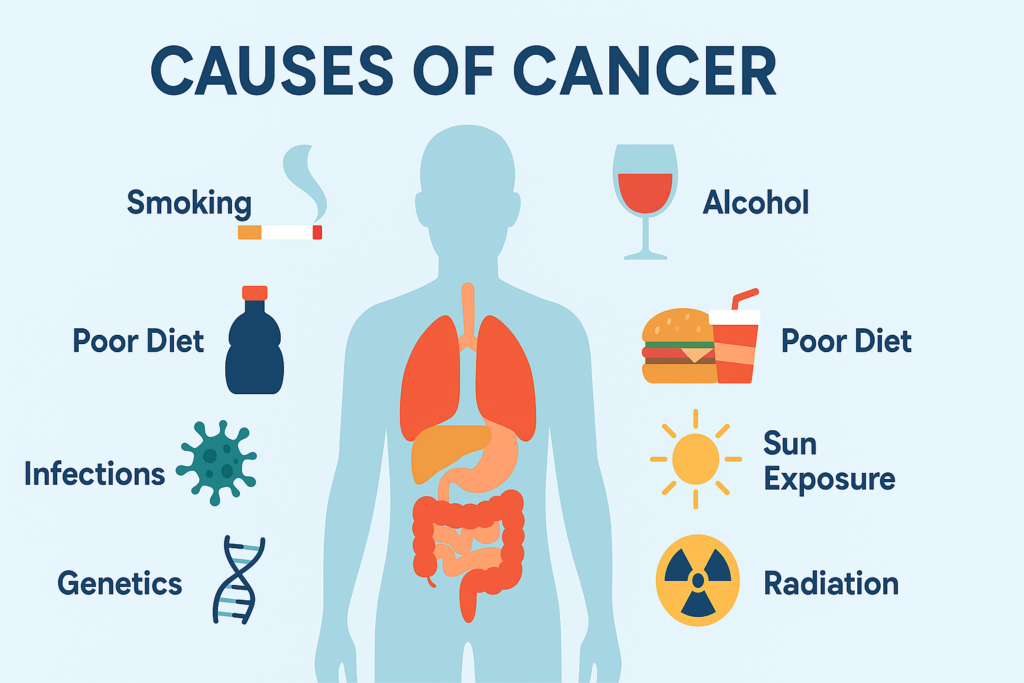

The development of cancer is a complex process, often resulting from an interplay of multiple factors over many years. While the precise cause of any individual cancer may not always be identifiable, research has illuminated numerous risk factors that can increase a person’s likelihood of developing the disease. It’s crucial to understand that having one or more risk factors does not guarantee cancer will develop, nor does the absence of known risk factors mean one is entirely immune (Mayo Clinic). Risk factors can be broadly categorized:

Lifestyle Factors (Modifiable):

- Tobacco Use: Smoking cigarettes, cigars, pipes, and using smokeless tobacco products is the single largest preventable cause of cancer and cancer deaths. Tobacco smoke contains numerous carcinogens (WHO).

- Alcohol Consumption: Drinking alcohol is linked to an increased risk of several cancers, including those of the mouth, throat, esophagus, liver, breast, and colorectum (WHO).

- Diet and Nutrition: Diets high in red and processed meats, saturated fats, and low in fruits, vegetables, and fiber have been associated with increased cancer risk.

- Obesity and Physical Inactivity: Being overweight or obese, and leading a sedentary lifestyle, are significant risk factors for various cancers, including breast, colon, endometrial, kidney, and esophageal cancers (Canadian Cancer Society).

- Excessive Sun Exposure and UV Radiation: Prolonged exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the sun or artificial sources like tanning beds can cause skin damage and increase the risk of skin cancer, including melanoma. Frequent blistering sunburns are particularly risky (Mayo Clinic).

- Unsafe Sex: Certain infections transmitted through unsafe sexual practices, such as some types of Human Papillomavirus (HPV), can increase the risk of cervical, anal, and oropharyngeal cancers.

Environmental Factors:

- Exposure to Carcinogens: Workplace or environmental exposure to certain chemicals (e.g., asbestos, benzene), industrial pollutants, and air pollution are known risk factors (WHO, Stanford Health Care).

- Radiation Exposure: Exposure to ionizing radiation, such as from radon gas in homes or certain medical procedures (though benefits often outweigh risks), can increase cancer risk.

Genetic Factors (Non-Modifiable/Predisposition):

- Inherited Gene Mutations: A small percentage of cancers are linked to inherited genetic mutations, such as BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations associated with breast and ovarian cancers. Having such a mutation significantly increases risk but doesn’t make cancer inevitable (Mayo Clinic).

- Family History of Cancer: A strong family history of certain cancers may suggest an inherited predisposition.

Other Key Factors:

- Age: Advancing age is one of the most significant risk factors for cancer. Cancer can take decades to develop, so most people diagnosed are 65 or older (Mayo Clinic).

- Chronic Health Conditions: Some chronic inflammatory conditions, like ulcerative colitis, can markedly increase the risk of developing specific cancers.

- Infectious Agents: Certain viruses (e.g., Human Papillomavirus – HPV, Hepatitis B and C viruses – HBV/HCV, Epstein-Barr virus – EBV) and bacteria (e.g., *Helicobacter pylori*) are linked to an increased risk of specific cancers like cervical, liver, and stomach cancer, respectively. Globally, infectious agents are estimated to cause a significant proportion of cancers, particularly in developing nations (Cancer in the Medically Underserved Population – PMC).

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that between 30-50% of all cancer cases are preventable through strategies like avoiding tobacco, maintaining a healthy lifestyle, and vaccination against cancer-causing infections (WHO).

Recognizing the Warning Signs: Common Symptoms of Cancer

Early detection of cancer significantly increases the chances of successful treatment. While many cancers may not cause symptoms in their early stages, being aware of general warning signs can prompt individuals to seek medical attention sooner. It is crucial to remember that many of these symptoms are non-specific and can be caused by a wide range of less serious conditions. However, if any of the following signs or symptoms are persistent, unexplained, or concerning, consulting a doctor is highly recommended (Mayo Clinic; American Cancer Society).

General signs and symptoms associated with, but not specific to, cancer include:

- Unexplained Weight Loss or Gain: Significant weight changes (e.g., 10 pounds or more) without changes in diet or exercise habits (NCI).

- Fatigue: Extreme tiredness or lack of energy that doesn’t improve with rest. This may occur because cancer cells use up much of the body’s energy supply (American Cancer Society).

- Lump or Area of Thickening: A new lump or an area of thickening that can be felt under the skin, particularly in the breast, testicles, lymph nodes, or soft tissues.

- Skin Changes: These can include jaundice (yellowing of skin and eyes), darkening or redness of the skin, sores that won’t heal, or changes in the size, color, shape, or thickness of a mole or wart (Mayo Clinic).

- Changes in Bowel or Bladder Habits: Persistent constipation, diarrhea, blood in the stool, changes in stool caliber, pain during urination, blood in the urine, or increased frequency or urgency.

- Persistent Cough or Hoarseness: A cough that doesn’t go away or unexplained hoarseness can be signs of lung or laryngeal cancer.

- Difficulty Swallowing (Dysphagia): Persistent problems with swallowing.

- Persistent Indigestion or Discomfort After Eating: Chronic indigestion or discomfort that is not relieved by usual remedies.

- Unexplained Bleeding or Bruising: This includes blood in sputum (coughed up mucus), stool, urine, abnormal vaginal bleeding or discharge, or nipple discharge (Cancer Research UK).

- Persistent, Unexplained Pain or Ache: Pain that does not go away or has no clear cause, such as persistent headaches or bone pain.

- Fever or Very Heavy Night Sweats: Recurrent fevers or drenching night sweats without a known infection (Cancer Research UK).

While awareness of these symptoms is important, self-diagnosis should be avoided. A medical professional is the only one who can determine the cause of such symptoms and recommend appropriate action. Proactive health management and timely consultation can make a significant difference in outcomes.

The Journey to Diagnosis: How Cancer is Identified

Diagnosing cancer is a comprehensive process that often begins when an individual presents with concerning symptoms or when a screening test suggests a potential abnormality. There is no single definitive test for all cancers; rather, a combination of assessments and procedures is typically employed to determine if cancer is present, identify its type, and understand its extent (NCI). This systematic approach ensures an accurate diagnosis, which is fundamental for effective treatment planning.

Initial Assessment

The diagnostic journey usually starts with:

- Medical History: The doctor will inquire about personal health history, including symptoms, past illnesses, lifestyle factors, and any family history of cancer.

- Physical Examination: A thorough physical exam is performed to check for any visible or palpable signs of disease, such as lumps, skin changes, or swollen lymph nodes.

Laboratory Tests (Blood, Urine, Other Fluids)

Various laboratory tests analyze samples of blood, urine, or other body fluids to detect abnormalities that might indicate cancer. While abnormal lab results are not a sure sign of cancer on their own, they provide valuable clues. According to the National Cancer Institute (NCI), common lab tests include:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): Measures the levels of different types of blood cells (red cells, white cells, platelets). Abnormalities can suggest certain blood cancers like leukemia or indicate how the body is responding to other conditions.

- Blood Chemistry Tests: Measure levels of various substances in the blood (e.g., enzymes, proteins, electrolytes, glucose, fats) released by organs and tissues. These tests can provide information about organ function (e.g., liver, kidneys) and may reveal abnormalities suggestive of cancer or treatment side effects.

- Tumor Markers: These are substances, often proteins, produced by cancer cells or by normal cells in response to cancer. Examples include PSA (Prostate-Specific Antigen) for prostate cancer and CA-125 for ovarian cancer. However, many tumor markers can be elevated in non-cancerous conditions, and not all cancers produce detectable markers, so they are often used in conjunction with other tests, or for monitoring treatment response.

- Cytogenetic Analysis: Examines chromosomes in cells from tissue, blood, or bone marrow samples for changes such as broken, missing, rearranged, or extra chromosomes, which can be indicative of certain genetic conditions or types of cancer.

- Immunophenotyping: Uses antibodies to identify cells based on the types of antigens (markers) on their surface. This is particularly useful for diagnosing, staging, and monitoring blood cancers like leukemias and lymphomas.

- Liquid Biopsy: An emerging technique that analyzes a blood sample for cancer cells (circulating tumor cells or CTCs) or pieces of DNA from tumor cells (circulating tumor DNA or ctDNA). Liquid biopsies hold promise for early cancer detection, treatment planning, and monitoring response to therapy or recurrence.

- Sputum Cytology: Microscopic examination of mucus coughed up from the lungs (sputum) to look for abnormal cells, which can help diagnose lung cancer.

- Urinalysis and Urine Cytology: Urinalysis checks for abnormal substances in urine, while urine cytology looks for abnormal cells shed from the urinary tract. These can aid in diagnosing bladder or kidney cancers.

Imaging Tests (Scans)

Imaging tests create pictures of the inside of the body, helping doctors to see if a tumor is present, determine its size and location, and assess if it has spread. Common imaging techniques include (Mayo Clinic; NCI):

- X-rays: Use low doses of radiation to create images of internal structures. Often a first-line imaging test.

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scan: Combines a series of X-ray images taken from different angles around the body and uses computer processing to create cross-sectional images (slices) of bones, blood vessels, and soft tissues. Provides more detailed information than plain X-rays.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Uses powerful magnets, radio waves, and a computer to produce detailed images of organs and soft tissues. Particularly useful for imaging the brain, spinal cord, and musculoskeletal system.

- Positron Emission Tomography (PET) Scan: Involves injecting a small amount of a radioactive tracer (often a form of sugar) into a vein. Cancer cells are often more metabolically active and absorb more of the tracer than normal cells, making them visible on the PET scan. PET scans can help detect cancer, see if it has spread, assess treatment effectiveness, or check for recurrence. Often combined with CT (PET-CT).

- Ultrasound (Sonography): Uses high-frequency sound waves to create real-time images of internal organs and tissues. A transducer is moved over the skin, and echoes are converted into images.

- Bone Scan: A type of nuclear scan that uses a radioactive tracer injected into a vein. The tracer collects in areas of abnormal bone activity, which can indicate cancer that has originated in or spread to the bones.

Biopsy (Often the Definitive Diagnostic Test)

In most cases, a biopsy is the only way to definitively diagnose cancer. A biopsy involves the removal of a small sample of suspicious tissue or cells, which is then examined under a microscope by a pathologist – a doctor specializing in identifying diseases by studying cells and tissues (NCI). Biopsies can be performed in several ways:

- Needle Biopsy: A needle is used to withdraw tissue or fluid. Examples include fine-needle aspiration (FNA), core needle biopsy (uses a larger needle to remove a core of tissue), and bone marrow aspiration/biopsy.

- Endoscopic Biopsy: A thin, lighted tube with a camera (endoscope) is inserted into a body opening (e.g., mouth for upper endoscopy, anus for colonoscopy). Tools can be passed through the endoscope to take tissue samples.

- Surgical Biopsy:

- Incisional biopsy: Only a part of the suspicious area is removed.

- Excisional biopsy: The entire suspicious area or tumor is removed, often with a margin of surrounding normal tissue.

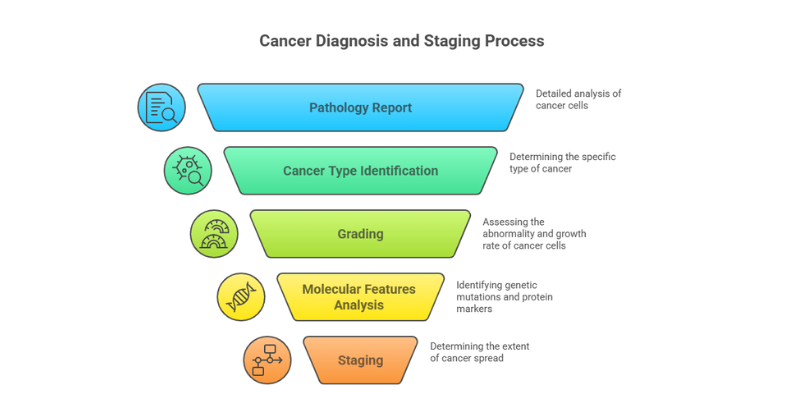

Pathology Report and Staging

Once a biopsy sample is obtained, the pathologist examines it and prepares a pathology report. This report is crucial and provides details such as:

- Cancer Type: The specific type of cancer cells identified (e.g., adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma).

- Grade: Describes how abnormal the cancer cells look under the microscope and how quickly the cancer is likely to grow and spread. Cancers are often graded on a scale (e.g., Grade 1 to 3 or 4).

- Molecular Features: May include information about specific genetic mutations or protein markers present in the cancer cells, which can guide targeted therapies.

If cancer is diagnosed, further tests are often done to determine the stage of the cancer. Staging describes the extent of the cancer – its size, whether it has spread to nearby lymph nodes, and whether it has metastasized to distant parts of the body. The TNM (Tumor, Node, Metastasis) system is commonly used. Staging is critical for determining the prognosis and selecting the most appropriate treatment plan (Stanford Health Care). A combination of these diagnostic tools allows healthcare professionals to build a comprehensive understanding of an individual’s cancer, paving the way for tailored and effective treatment.

Navigating Treatment Landscapes: Modern Approaches to Cancer Care

The treatment of cancer is a highly specialized field that has seen remarkable advancements. Modern cancer care typically involves a multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach, where specialists from various fields—such as surgical oncology, medical oncology, radiation oncology, pathology, and radiology—collaborate to develop an individualized treatment plan. The choice of treatment depends on several factors, including the type and stage of cancer, the patient’s overall health and preferences, and the specific characteristics of the tumor, such as its genetic makeup.

Main Pillars of Cancer Treatment

Traditional cancer treatments form the backbone of many therapeutic strategies:

- Surgery: This involves the physical removal of cancerous tissue. Surgery can be used to diagnose cancer (biopsy), stage cancer, remove a tumor (curative surgery), relieve symptoms caused by a tumor (palliative surgery), reduce the risk of cancer (preventative surgery), or restore appearance or function (reconstructive surgery).

- Chemotherapy: This uses cytotoxic drugs to kill cancer cells or slow their growth by interfering with their ability to divide. Chemotherapy can be administered intravenously (IV), orally, or via injection. It may be used as a primary treatment, before surgery (neoadjuvant chemotherapy) to shrink a tumor, after surgery (adjuvant chemotherapy) to kill any remaining cancer cells, or to manage advanced cancer (palliative chemotherapy). Common side effects stem from the drugs’ impact on rapidly dividing healthy cells and can include fatigue, nausea, hair loss, and increased risk of infection, though many of these can be managed.

- Radiation Therapy (Radiotherapy): This treatment uses high-energy rays (like X-rays) or particles to destroy cancer cells or damage their DNA, preventing them from growing or multiplying. Radiation can be delivered from a machine outside the body (external beam radiation) or from radioactive material placed inside the body near cancer cells (internal radiation or brachytherapy). Similar to chemotherapy, it can be used for curative or palliative purposes. Side effects depend on the area being treated and can include skin changes, fatigue, and site-specific issues.

Newer and Specialized Treatments

The field of oncology is rapidly evolving with innovative therapies offering more targeted and effective options:

- Immunotherapy: This groundbreaking approach harnesses the body’s own immune system to recognize and fight cancer cells.

- Mechanism: Some immunotherapies, like checkpoint inhibitors, help the immune system overcome “brakes” that cancer cells use to evade detection. Others, like CAR T-cell therapy, involve genetically engineering a patient’s T-cells to specifically target and destroy cancer cells. Therapeutic cancer vaccines aim to stimulate an immune response against cancer cells.

- Success: The average response rate to immunotherapy drugs can range from 20% to 50%, varying significantly by cancer type and specific drug (Cochise Oncology). However, when effective, immunotherapy can lead to durable, long-lasting remissions. For example, in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the immunotherapy drug pembrolizumab has been shown to increase the average 5-year survival rate from around 5.5% (with traditional chemotherapy) to about 15% in certain patient populations (Cochise Oncology, referencing UCLA research).

- Targeted Therapy: These drugs are designed to target specific molecules (genes, proteins, or the tissue environment) that are involved in the growth, progression, and spread of cancer cells.

- Mechanism: Unlike chemotherapy, which affects all rapidly dividing cells, targeted therapies are more selective. Identifying appropriate targets often requires molecular testing of the tumor. Examples include EGFR inhibitors for certain lung cancers, ALK inhibitors for ALK-positive NSCLC, and PARP inhibitors for cancers with BRCA mutations.

- Survival Improvements: Targeted therapies have significantly improved outcomes for patients with specific genetic alterations. For instance, a study on advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) showed that patients receiving targeted therapy (specifically EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors) had a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 13 months compared to 7 months for those receiving chemotherapy, and a median overall survival (OS) of 45 months versus 17 months, respectively (Impact of Targeted Therapy on Survival in NSCLC – PMC).

- Hormone Therapy (Endocrine Therapy): Used for cancers that are fueled by hormones, such as certain types of breast cancer (estrogen-receptor positive) and prostate cancer (androgen-sensitive). Hormone therapy works by blocking the body’s ability to produce these hormones or by interfering with how hormones affect cancer cells.

- Stem Cell Transplant (Bone Marrow Transplant): Primarily used for blood cancers (leukemia, lymphoma, myeloma) and some other conditions. This procedure allows patients to receive very high doses of chemotherapy or radiation to eradicate cancer cells. Afterward, the patient receives an infusion of healthy blood-forming stem cells (from themselves, collected earlier, or from a donor) to restore their bone marrow.

Precision/Personalized Medicine

This overarching approach aims to tailor treatment to the individual characteristics of each patient’s cancer. By analyzing the genomic profile (DNA and RNA) of a tumor, doctors can identify specific mutations or biomarkers that may predict how a cancer will behave and which treatments are most likely to be effective, leading to more personalized and potent therapeutic strategies.

Palliative Care

Palliative care is specialized medical care focused on providing relief from the symptoms and stress of a serious illness, like cancer. The goal is to improve quality of life for both the patient and the family. Palliative care can be provided alongside curative treatment at any stage of the illness, not just at the end of life. It addresses physical symptoms like pain and nausea, as well as emotional, social, and spiritual needs.

Clinical Trials

Clinical trials are research studies that test new treatments or new ways of using existing treatments. Participating in a clinical trial can offer patients access to cutting-edge therapies that are not yet widely available. They are essential for advancing cancer care and discovering better ways to prevent, diagnose, and treat cancer.

Critical Insights on Treatment

Modern cancer treatment is increasingly personalized, moving beyond a one-size-fits-all approach. The integration of genomic testing, immunotherapy, and targeted therapies is transforming outcomes for many cancers. However, access to these advanced treatments and the expertise of multidisciplinary teams can vary, highlighting the ongoing need for equitable healthcare.

The Forefront of Discovery: Latest Advances in Cancer Research and Treatment (2024-2025 Focus)

The fight against cancer is characterized by relentless innovation and a rapidly expanding understanding of its complex biology. The period between 2024 and 2025 has been particularly dynamic, with significant breakthroughs and promising research directions heralding new hope for patients. Key themes include the power of personalized medicine, the refinement of immunotherapies, the advent of AI in oncology, and a strong focus on early detection and addressing health disparities.

Overall Themes and Progress (2024 Review & 2025 Forecast)

Several overarching trends have defined recent cancer research, as highlighted by leading organizations like the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR), the National Cancer Institute (NCI), and the Mayo Clinic:

- Accelerated Drug Approvals: In 2024, the FDA approved oncology drugs for over 50 indications, including 11 first-in-class therapeutics, showcasing the rapid translation of research into clinical practice (AACR Experts Forecast 2025).

- Personalized Cancer Vaccines: Significant strides have been made in developing vaccines that are tailored to an individual’s tumor. mRNA technology, famously used for COVID-19 vaccines, is being leveraged to create vaccines for cancers like head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) and pancreatic cancer, designed to prime the immune system to target cancer cells and reduce recurrence risk (AACR Year in Review 2024; World Economic Forum – 12 Breakthroughs). Some trials are expected to complete by 2027.

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) Revolution:

- Drug Discovery: AI algorithms like AlphaFold, which predicts protein structures, are accelerating the identification of new drug targets (AACR Year in Review 2024).

- Early Detection & Prediction: AI models are being developed to predict cancer risk years in advance, for instance, by analyzing low-dose CT scans for lung cancer or H&E stained pathology slides to impute transcriptomic profiles, potentially spotting treatment resistance earlier (World Economic Forum; AACR Experts Forecast 2025).

- Biomarker Identification & Trial Design: AI is helping to identify predictive biomarkers for immunotherapy and optimize clinical trial designs.

- Evolution of Precision Medicine: Efforts are intensifying to target previously “undruggable” mutations, such as various KRAS alterations (G12D, G12V, pan-RAS inhibitors), which are common across multiple tumor types, including pancreatic cancer. This offers hope for cancers that were previously very difficult to treat with a precision approach (AACR Experts Forecast 2025).

- Immunotherapy Refinements: Research is focused on overcoming resistance to existing immunotherapies, exploring new combination strategies, and expanding their use. The approval of the first tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) cell therapy for metastatic melanoma marks a significant step for solid tumor treatment (AACR Year in Review 2024; AACR Experts Forecast 2025).

- Advancements in Liquid Biopsies: The use of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) from blood samples is becoming more sophisticated for early detection, monitoring treatment response, guiding dose escalation in clinical trials, and detecting minimal residual disease (AACR Year in Review 2024).

- Improved Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs): ADCs, which deliver potent chemotherapy directly to cancer cells via an antibody, are being designed with novel targets, more stable linkers, and payloads with higher therapeutic indices to reduce toxicity (AACR Experts Forecast 2025).

- Deeper Understanding of Cancer Biology: Research into cancer development, such as the role of clonal hematopoiesis (age-related blood stem cell changes that can precede leukemia), is providing new avenues for early intervention and prevention (AACR Year in Review 2024).

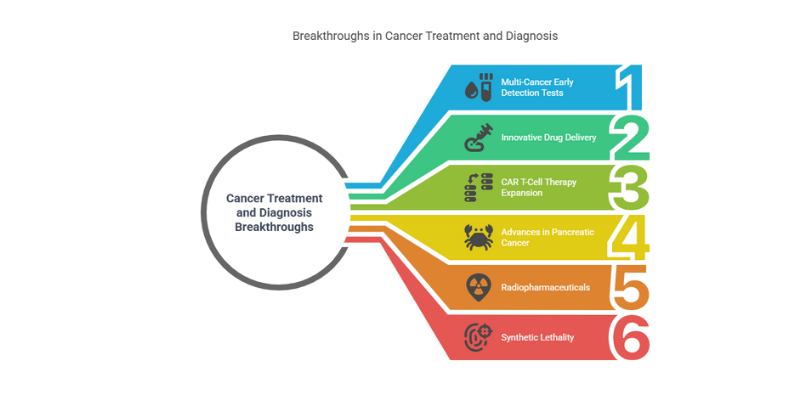

Specific Breakthroughs and Emerging Therapies

Beyond these broad themes, several specific advancements are generating excitement:

- Multi-Cancer Early Detection (MCED) Tests: Significant progress is being made on blood tests capable of identifying multiple types of cancer at an early stage by analyzing blood proteins or ctDNA. One such test reportedly identified 93% of stage 1 cancers in men and 84% in women in a small screening (World Economic Forum). The Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health (ARPA-H) is also supporting the development of at-home MCED tests using breath or urine samples (AACR Year in Review 2024).

- Innovative Drug Delivery: The introduction of a subcutaneous injection for Atezolizumab (an immunotherapy drug), reducing administration time from up to an hour (IV) to just seven minutes, exemplifies efforts to improve patient convenience and healthcare efficiency (World Economic Forum).

- CAR T-Cell Therapy Expansion and Evolution: While highly successful for certain blood cancers like leukemia, CAR T-cell therapy is being adapted for solid tumors. Development is also underway for allogeneic (“off-the-shelf”) CAR T-cells derived from healthy donors, which could improve scalability and accessibility (AACR Experts Forecast 2025). The FDA is monitoring a rare risk of secondary T-cell malignancies, but for many, the benefits are profound.

- Advances in Pancreatic Cancer: This notoriously difficult-to-treat cancer is seeing new diagnostic approaches, such as tests analyzing biomarkers in extracellular vesicles or the “PAC-MANN” test using a single drop of blood for early detection. Research continues into overcoming its significant treatment resistance (World Economic Forum).

- Radiopharmaceuticals (Targeted Radionuclide Therapy): This involves using radioactive particles designed to specifically seek out and destroy cancer cells (theranostics – combining therapy and diagnostics). This approach shows promise for delivering localized radiation with potentially fewer systemic side effects (Nature – Innovative cancer therapies).

- Synthetic Lethality: This strategy exploits specific genetic vulnerabilities present only in cancer cells. If a cancer cell has a defect in one DNA repair pathway, drugs targeting a parallel pathway can selectively kill these cancer cells while sparing normal cells. PARP inhibitors are a prime example.

Clinical Trial Trends for 2025

Experts anticipate several key trends in clinical trials for 2025 (AACR Experts Forecast 2025):

- Neoadjuvant Therapies: An increased focus on trials evaluating immunotherapies and targeted treatments given before surgery, aiming to shrink tumors, assess treatment response early, and potentially eradicate micrometastases.

- ctDNA-Guided Trials: Greater incorporation of ctDNA analysis to monitor treatment response, guide dose adjustments, and make go/no-go decisions in early-phase trials.

- Primary Prevention Vaccines: Trials for vaccines aimed at preventing cancer in high-risk individuals, such as those with Lynch syndrome, are an emerging area of interest.

Hope on the Horizon

These advancements, spanning early detection, AI-driven insights, novel therapeutics, and refined treatment strategies, underscore a period of unprecedented progress in oncology. While challenges remain, particularly in ensuring equitable access and managing treatment complexities, the pace of discovery offers tangible hope for transforming cancer from a often-fatal disease to a manageable, and in some cases, curable condition.

Empowerment Through Prevention: Reducing Your Cancer Risk

While cancer can arise from factors beyond our control, a significant portion of cancer cases and deaths are preventable through proactive lifestyle choices and medical interventions. The World Health Organization estimates that 30-50% of all cancers can be prevented (WHO). This underscores the immense power individuals have to reduce their risk.

Lifestyle Choices (Evidence-Based):

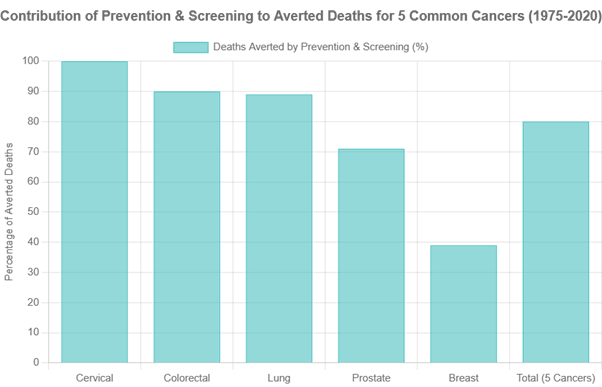

- Tobacco Cessation: Avoiding tobacco in all its forms (cigarettes, cigars, smokeless tobacco) is the single most impactful cancer prevention strategy. A landmark modeling study by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) indicated that smoking cessation alone accounted for 3.45 million averted lung cancer deaths in the U.S. between 1975 and 2020 (NCI Press Release, Dec 5, 2024).

- Healthy Diet: Consuming a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean protein, while limiting processed and red meats, sugary drinks, and unhealthy fats, can significantly lower cancer risk. The American Cancer Society notes that excess body weight, poor diet, alcohol consumption, and physical inactivity collectively contribute to over 15% of cancer cases and deaths (ACS, Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2025-2026).

- Regular Physical Activity: Engaging in regular physical activity helps maintain a healthy weight and has independent cancer-protective effects. Aim for at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity per week, along with muscle-strengthening activities.

- Maintain a Healthy Weight: Obesity is a known risk factor for at least 13 different types of cancer. Maintaining a healthy body weight through diet and exercise is crucial.

- Limit Alcohol Consumption: If you choose to drink alcohol, do so in moderation. The evidence suggests there is no “safe” level of alcohol consumption regarding cancer risk, so less is always better (WHO).

- Sun Protection: Protect your skin from excessive ultraviolet (UV) radiation by using sunscreen (SPF 30 or higher), wearing protective clothing, seeking shade during peak sun hours, and avoiding tanning beds.

Vaccination:

- Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccine: HPV is a common virus that can cause several types of cancer, most notably cervical cancer. The HPV vaccine is highly effective in preventing infections with cancer-causing HPV types. Studies have shown remarkable success:

- Nationwide cohort studies indicate that HPV vaccination can reduce the incidence rate of cervical cancer by 86% to nearly 100% among individuals vaccinated at a young age (before exposure) (Real-World Effectiveness of HPV Vaccination – PMC; STAT News – HPV vaccine study).

- Projections suggest that 80% to 100% vaccination rates, including catch-up vaccinations, could prevent nearly 50 million cervical cancer cases globally by 2100 (Our World in Data – HPV Vaccination).

- Cervical cancer deaths in young women have plummeted, with one study noting a 62% drop in the last decade, likely attributable to HPV vaccination (MUSC Hollings Cancer Center).

- Hepatitis B Vaccine: Chronic Hepatitis B infection is a major cause of liver cancer. The Hepatitis B vaccine effectively prevents HBV infection and, consequently, a significant proportion of liver cancers.

Cancer Screening (for Early Detection and Prevention):

Cancer screening plays a dual role: it can detect cancer at an early stage when it is most treatable, and in some cases, it can prevent cancer altogether by identifying and removing precancerous lesions (e.g., polyps during a colonoscopy, precancerous cervical cells during a Pap test). NIH research underscores that prevention and screening interventions accounted for 4.75 million (or 80%) of the 5.94 million averted deaths from breast, cervical, colorectal, lung, and prostate cancers between 1975 and 2020 (NCI Press Release, Dec 5, 2024). Commonly recommended screenings include:

- Breast Cancer: Mammography for women, with guidelines varying by age and risk factors.

- Colorectal Cancer: Colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, or stool-based tests (like FIT) starting from age 45-50, or earlier for those with higher risk.

- Cervical Cancer: Pap tests and/or HPV tests for women, starting from age 21-25.

- Lung Cancer: Low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) for individuals at high risk (e.g., current or former heavy smokers within a certain age range).

Research highlights the cost-effectiveness of many screening programs. For instance, studies on breast cancer screening show that earlier initiation can be cost-saving by reducing the need for more expensive treatments for advanced cancers (JAMA Network Open – Cost-Effectiveness of Breast Cancer Screening). Similarly, various colorectal cancer screening methods have proven to be cost-effective (PMC – Cost-effectiveness of CRC screening).

Prevention truly is the most cost-effective long-term strategy for cancer control. By embracing these evidence-based strategies, individuals can take significant steps to safeguard their health and contribute to reducing the global burden of cancer.

Beyond Treatment: Survivorship, Quality of Life, and Support

The journey with cancer does not end when active treatment concludes. Cancer survivorship, which begins at the moment of diagnosis and continues throughout a person’s life, encompasses a wide range of ongoing physical, psychological, social, and spiritual challenges and adjustments. With advancements in detection and treatment, the number of cancer survivors is growing, bringing increased focus on their long-term health and quality of life.

Psychological and Emotional Impact

A cancer diagnosis and its treatment can have a profound psychological and emotional toll. Common experiences include:

- Fear of Recurrence: One of the most pervasive anxieties among survivors is the fear that cancer will return.

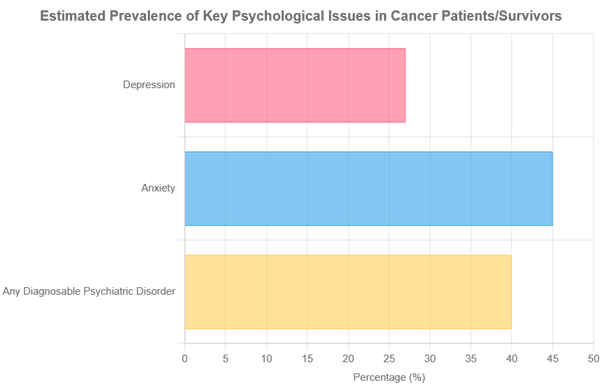

- Anxiety and Depression: Studies indicate that a significant percentage of cancer patients and survivors experience clinical anxiety and/or depression. Prevalence rates for depression among cancer patients are estimated to be up to 20-27%, and for anxiety around 10-45%, depending on the study and cancer type (PMC – Mental health needs in cancer; Nଭ Network – Mental Health Impacts). Some analyses suggest 35-40% of cancer patients may have a diagnosable psychiatric disorder.

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Symptoms: The traumatic nature of a cancer diagnosis and intensive treatments can lead to PTSD-like symptoms in some survivors.

- Grief, Guilt, and Existential Concerns: Survivors may grieve lost health, abilities, or future plans, and grapple with existential questions.

Access to mental health support, including counseling, therapy, and support groups, is crucial for addressing these challenges and fostering psychological well-being (PMC – Psychological Health in Cancer Survivors).

Physical Long-Term and Late Effects

Cancer treatments, while life-saving, can cause lasting physical effects that may emerge during treatment and persist (long-term effects) or develop months or even years after treatment completion (late effects) (PMC – Physical and Psychological Long-Term Effects). These can include:

- Chronic Fatigue: Persistent and debilitating tiredness not relieved by rest.

- Chronic Pain: Ongoing pain related to surgery, nerve damage (neuropathy), or other treatment sequelae.

- Neuropathy: Numbness, tingling, or pain, often in the hands and feet, due to nerve damage from certain chemotherapies.

- Lymphedema: Swelling, typically in an arm or leg, caused by damage to or removal of lymph nodes.

- Cognitive Changes (“Chemo Brain”): Difficulties with memory, concentration, and mental clarity.

- Sexual Dysfunction: Issues related to libido, fertility, or sexual function due to hormonal changes, surgery, or other treatments.

- Cardiovascular Issues: Some treatments can increase the risk of heart problems later in life.

- Endocrine Problems: Hormonal imbalances affecting thyroid function, bone health, etc.

- Secondary Cancers: A small but increased risk of developing a new, unrelated cancer due to previous cancer treatments like radiation or chemotherapy.

Ongoing medical surveillance and management are essential for identifying and addressing these long-term and late effects.

Quality of Life (QoL)

Improving and maintaining a good quality of life is a primary goal for cancer survivors. QoL is a multifaceted concept encompassing physical health, functional ability, psychological state, social relationships, and personal beliefs (PMC – Factors Associated With HRQoL Among Survivors). Research consistently shows that factors like regular physical activity, strong social support, effective symptom management, and psychological resilience can positively impact QoL in survivors (ACS – Physical Activity and QoL; Nature – Resilience and QoL).

Support Systems

Navigating survivorship can be challenging, and robust support systems are vital. These include:

- Family and Friends: Emotional and practical support from loved ones.

- Support Groups: Connecting with other survivors can provide shared understanding, coping strategies, and reduced feelings of isolation.

- Healthcare Team: Oncology nurses, social workers, psychologists, and psycho-oncology services play a critical role in providing comprehensive support, from information and counseling to resource navigation (MD Anderson – Social & Emotional Impacts).

The survivorship phase is increasingly recognized as an integral part of the cancer care continuum. The focus is shifting towards empowering survivors to manage long-term effects, optimize their quality of life, and embrace a “new normal” filled with resilience and hope.

Did you know that complaining can impact your brain? If you’re interested in learning more, click here.

Addressing Inequities: Striving for Fair Cancer Outcomes for All

Despite remarkable progress in cancer research and treatment, the benefits of these advancements are not shared equally across all populations. Cancer disparities—differences in cancer burden, including incidence, prevalence, mortality, survivorship, quality of life, screening rates, and stage at diagnosis—persist and represent a significant public health challenge (AACR – State of U.S. Cancer Disparities 2024). Addressing these inequities is crucial for achieving true progress against cancer.

Types of Disparities:

- Racial and Ethnic Disparities:

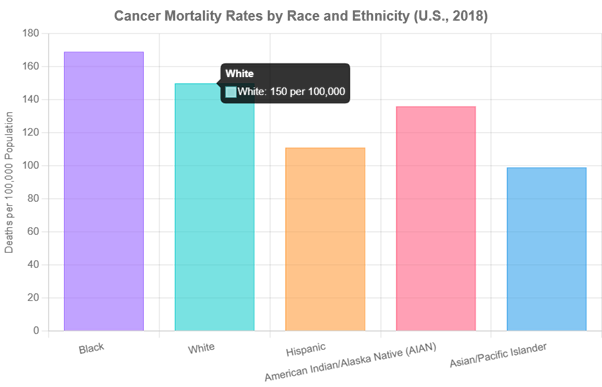

- Data consistently show varying cancer incidence and mortality rates among different racial and ethnic groups. For instance, in the U.S., Black individuals often experience higher mortality rates for many common cancers (e.g., breast, prostate, colorectal) and are diagnosed at later stages, even when incidence rates are similar to or lower than White individuals (KFF – Racial Disparities in Cancer).

- American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) populations face disproportionately high incidence rates for certain cancers like colorectal, kidney, liver, and stomach cancer compared to non-Hispanic White populations (AACR – State of U.S. Cancer Disparities 2024).

- Socioeconomic Disparities:

- Individuals with lower socioeconomic status (SES)—often measured by income, education, and insurance coverage—generally experience higher cancer mortality rates and are diagnosed at later stages. This is linked to reduced access to quality healthcare, including prevention services, screening, timely diagnosis, and advanced treatments (PMC – Socioeconomic Deprivation and Cancer Outcomes).

- Follicular lymphoma patients in lower SES neighborhoods, for example, had an 84% higher risk of death than those in higher SES areas (UC Berkeley Public Health).

- Geographic Disparities: Access to specialized cancer care, Palliative care services, and participation in clinical trials can be limited in rural or remote areas compared to urban centers, leading to disparities in outcomes.

Note: Data for AIAN and Asian/Pacific Islander groups often have smaller sample sizes, which can affect statistical stability. Data from KFF (2018 data).

Contributing Factors to Cancer Disparities:

The roots of cancer disparities are complex and multifactorial:

- Social Determinants of Health (SDOH): These are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age. Factors like limited access to healthy food, safe housing, quality education, stable employment, and exposure to environmental hazards significantly influence health outcomes (Cancer Research Institute – Disparities in Underserved Communities).

- Barriers to Healthcare Access: Lack of health insurance or underinsurance, transportation difficulties, cost of care, and distance to healthcare facilities can prevent individuals from receiving timely prevention, screening, diagnosis, and treatment.

- Mistrust of the Healthcare System: Historical and ongoing experiences of discrimination and unethical practices can lead to mistrust among certain populations, affecting their willingness to seek care.

- Cultural Factors and Health Literacy: Differences in cultural beliefs, language barriers, and limited health literacy can impact understanding of cancer information, adherence to treatment, and navigation of the healthcare system.

- Underrepresentation in Clinical Trials: Racial and ethnic minorities, as well as other underserved groups, are often underrepresented in cancer clinical trials, which can limit the generalizability of research findings and access to novel therapies.

- Differences in Exposure to Risk Factors: Underserved populations may have higher exposure to tobacco, unhealthy diets, and environmental carcinogens due to socioeconomic and environmental factors. For example, infectious agents like HPV and Hepatitis B/C cause a higher proportion of cancers in developing nations and some underserved communities (PMC – Cancer in the Medically Underserved).

Addressing the Gaps Towards Health Equity:

Achieving health equity, where everyone has a fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible, requires a multi-pronged approach (WHO – Global Cancer Burden; NCI – Cancer Disparities):

- Culturally Sensitive Care and Communication: Tailoring health information and care delivery to meet the cultural and linguistic needs of diverse populations.

- Community-Based Interventions: Partnering with communities to develop and implement targeted programs for prevention, screening, and patient navigation.

- Policy Changes: Advocating for policies that expand health insurance coverage, reduce healthcare costs, address SDOH, and promote environmental justice.

- Increasing Diversity: Enhancing diversity in the healthcare workforce and among clinical trial participants to ensure care is equitable and research is inclusive.

- Equitable Implementation of Advances: Ensuring that new technologies and treatments are accessible to all populations, not just those with more resources.

The global cancer burden is predicted to grow significantly, with over 35 million new cases expected in 2050, a 77% increase from 2022. This increase will disproportionately affect low and middle-income countries and underserved populations within wealthier nations (WHO – Global Cancer Burden). Concerted efforts to address these disparities are not just a matter of social justice but a public health imperative.

Empowering Knowledge, Inspiring Action: Your Role in the Fight Against Cancer

This journey through the multifaceted world of cancer has taken us from understanding its cellular origins and diverse manifestations to exploring its causes, symptoms, the intricacies of diagnosis and treatment, the power of prevention, and the exciting horizon of ongoing research. The landscape of cancer care is one of constant evolution, driven by scientific inquiry and a collective commitment to improving lives.

The Power of Information and Proactivity

Knowledge is a powerful ally in the fight against cancer. For everyone, understanding risk factors and preventive measures can significantly reduce the likelihood of developing the disease. Being aware of potential symptoms allows for earlier consultation and diagnosis, which often leads to better outcomes. For patients and their families, credible information empowers them to ask informed questions, participate actively in treatment decisions, advocate for comprehensive care, and build essential support networks.

Message of Hope and Progress

The narrative of cancer is increasingly one of hope. Scientific advancements are continuously refining our ability to detect cancer earlier, treat it more effectively, and improve the quality of life for survivors. The dedication of researchers, healthcare professionals, patient advocates, and countless individuals touched by cancer fuels this progress. Breakthroughs in immunotherapy, targeted therapies, personalized medicine, and early detection technologies are not just abstract concepts; they are translating into tangible benefits for patients worldwide.

Call to Action:

- For the General Public: Embrace preventive lifestyle choices – avoid tobacco, maintain a healthy diet and weight, be physically active, protect yourself from the sun, and limit alcohol. Participate in recommended cancer screenings and be vigilant about persistent or unusual symptoms. If you are able, consider supporting cancer research and advocacy organizations that work tirelessly to advance the field and support patients.

- For Patients and Families: Stay informed about your specific cancer type and treatment options. Do not hesitate to seek second opinions if you feel it’s necessary. Actively participate in discussions with your healthcare team and make shared decisions about your care. Utilize available support services – emotional, psychological, and practical – and remember that you are not alone. Sharing your experiences, when you are ready, can also offer comfort and guidance to others on similar paths.

- For Medical Professionals: Continue your commitment to lifelong learning and applying the latest evidence-based practices in cancer prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship care. Advocate for your patients, particularly those facing disparities, to ensure they receive equitable and high-quality care. Contribute to the body of knowledge through research, mentor the next generation, and champion public health initiatives aimed at reducing the cancer burden.

“Together, through knowledge, action, and unwavering hope, we can continue to make profound strides against cancer, transforming the future for millions worldwide. The journey is ongoing, but progress is undeniable, and every step forward brings us closer to a world where cancer is increasingly preventable, treatable, and ultimately, conquerable.”

This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Always consult with a qualified healthcare professional for any health concerns or before making any decisions related to your health or treatment.